Our thyroid is a small but central organ that controls metabolism, regulates body temperature, promotes growth and plays a crucial role in the development of the nervous system, especially during pregnancy and early childhood. Its function depends on essential nutrients that are necessary for the production and action of thyroid hormones. A deficiency or excess of certain nutrients can cause imbalances, resulting in symptoms such as fatigue, weight fluctuations or concentration problems. Thyroid disorders, especially hypothyroidism, are common worldwide and affect millions of people.

Functional disorders of the thyroid

Hyperthyroidism (hyperthyroidism)

Hyperthyroidism is characterized by excessive hormone production, which accelerates the metabolism. The main causes are Graves' disease, toxic goitre or autonomous adenomas. A high iodine intake can also trigger hyperfunction (iodine-Basedow effect). Typical symptoms are nervousness, insomnia, palpitations, weight loss despite appetite, trembling and sweating.

Underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism)

Hypothyroidism is more common and is characterized by insufficient hormone production, which slows down the metabolism. They affect up to 10% of the population, mainly women and older people. The causes are autoimmune disorders (e.g. Hashimoto's thyroiditis), iodine deficiency, thyroid surgery or certain medications (e.g. amiodarone, lithium). Chronic deficiencies of iodine, selenium, zinc or iron can also contribute to hypothyroidism. The symptoms of hypothyroidism develop gradually and include fatigue, weight gain, sensitivity to cold, dry skin, hair loss, constipation, concentration problems and elevated cholesterol levels.

Meaning of nutrition

Nutrition plays a central role in the thyroid gland, as it provides essential micronutrients that are necessary for hormone production and regulation. The thyroid gland produces the hormones T3 (triiodothyronine) and T4 (thyroxine), which influence almost all bodily functions. Their synthesis and effect depend on a sufficient supply of essential nutrients. A deficiency can impair the function of the thyroid gland and lead to disease in the long term.

Anatomy and hormone production

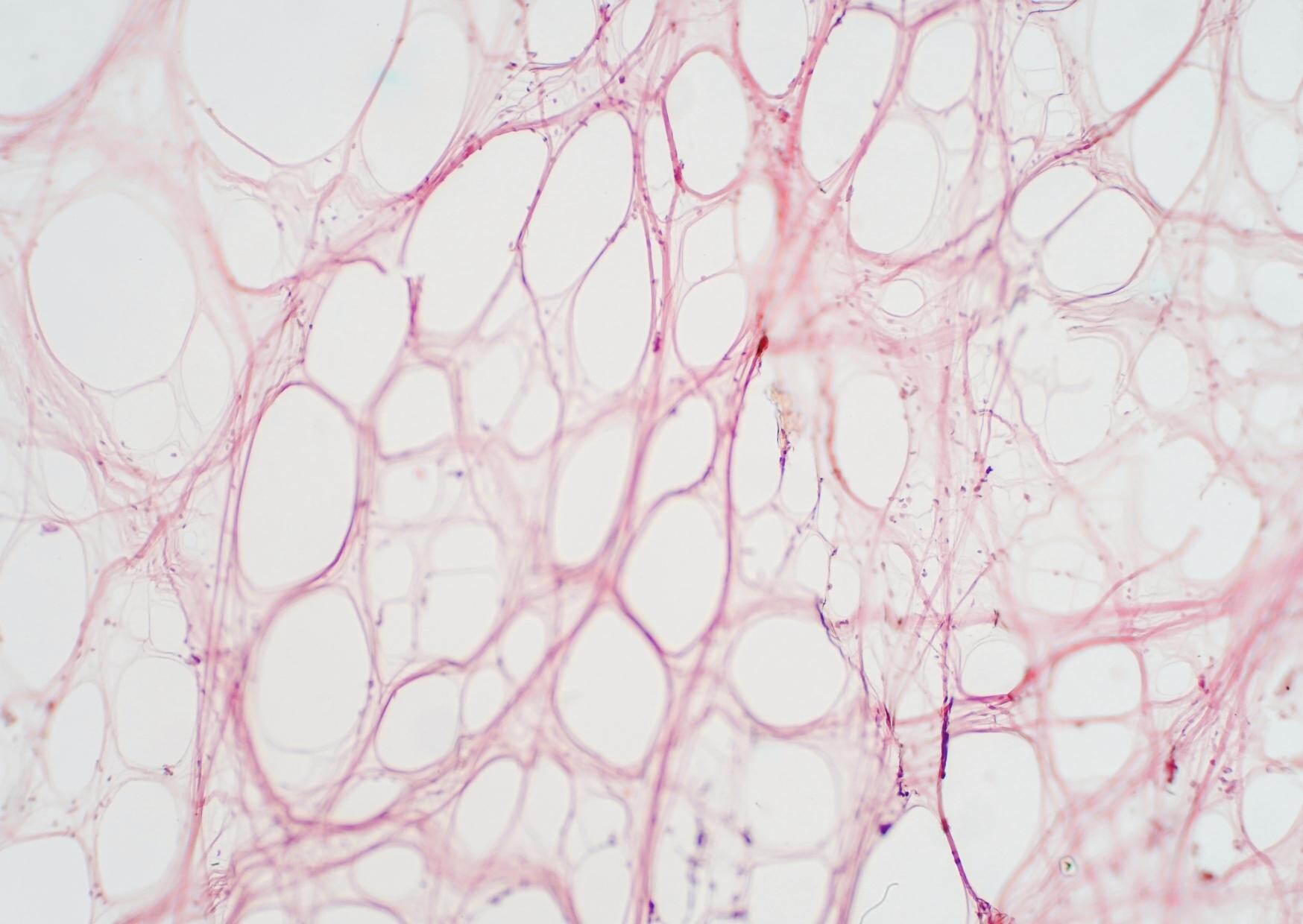

The thyroid gland is a butterfly-shaped organ consisting of two lobes connected by the isthmus. The functional units of the thyroid gland are the follicles, which consist of a single cell layer of thyrocytes (thyroid cells). Inside the follicles is colloid, a gel-like substance that contains thyroglobulin, the starting protein for thyroid hormones.

Important nutrients

Tyrosine

Tyrosine is a non-essential amino acid that the body can produce from phenylalanine or absorb from protein-rich foods. It is important for the thyroid, as it provides the basis for the hormones T3 (triiodothyronine) and T4 (thyroxine). In thyroid tissue, tyrosine is incorporated into the protein thyroglobulin, which is stored in the follicular lumen. The enzyme thyroperoxidase (TPO) binds iodine to tyrosine residues in thyroglobulin and thus forms monoiodotyrosine (MIT) and diiodotyrosine (DIT), the precursors of T3 and T4. Two DIT molecules form T4, one MIT and one DIT form T3. This process is not possible without tyrosine.

- Possible problems: A deficiency can impair thyroid hormone synthesis and lead to hypofunction. In addition, reduced stress resistance and listlessness can occur, as the production of neurotransmitters is restricted.

- Food sources: A balanced, protein-rich diet ensures a sufficient supply of this amino acid. The daily requirement for tyrosine is 10-15 mg per kilogram of body weight, depending on individual factors (e.g. age, gender, activity level).

Iodine

This essential trace element is the main component of the thyroid hormones T3 and T4. Without iodine, their synthesis is impossible. The sodium iodide symporter (NIS) transports iodine into the thyroid cells, where it is oxidized by thyroperoxidase (TPO) and incorporated into hormone production. Iodine deficiency can reduce hormone production, slow down the metabolism and cause symptoms of hypothyroidism.

- Possible problems: Iodine deficiency is one of the most common causes of thyroid diseases such as goitre or hypothyroidism worldwide.

- Food sources: Iodine is mainly found in foods that come from water, whereby the daily requirement according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the German Nutrition Society (DGE) is 150-200 mg per day for adults and 250 mg per day for pregnant women/breastfeeding mothers.

Selenium

As an essential trace element, selenium is involved in the activation of thyroid hormones and is a co-factor of deiodinases, which convert inactive T4 into active T3. Selenium protects the thyroid gland from oxidative stress as it is a component of antioxidant enzymes.

- Possible problems: A deficiency can reduce the conversion of T4 to T3 and weaken the immune defense of the thyroid gland.

- Food sources: Selenium is found in seafood, animal foods (meat, eggs), mushrooms and paranuts. The recommended daily intake for adults is 55-70 μg of selenium per day, and 60-70 μg per day for pregnant or breastfeeding women.

Zinc

Zinc is crucial for the production and release of thyroid hormones. It promotes the synthesis of TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone) in the pituitary gland and is essential for the function of thyroid hormone receptors in target tissues.

- Possible problems: A lack of zinc can inhibit thyroid hormone production and impair immune function.

- Food sources: A combination of animal and plant sources can provide a good supply of zinc, with zinc from animal sources being better absorbed. The recommended daily intake for adult women is 7-10 mg zinc per day, for adult men 11-15 mg zinc per day. Pregnant/breastfeeding women should take 10-13 mg of zinc per day.

- Possible problems: Low iron levels can contribute to hypothyroidism and exacerbate symptoms such as fatigue and concentration problems.

- Food sources: Iron is found in many foods, but can be divided into two main categories: Häm iron (mainly in animal sources) and non-Häm iron (from plant sources). H¨m iron is better absorbed by the body, which is why animal foods offer a higher bioavailability.

- Possible problems: A deficiency intensifies inflammatory processes and can promote autoimmune diseases.

- Food sources: Vitamin D3 is mainly produced by sunlight on the skin, but can be partially absorbed through food as a fatty vitamin. It is mainly present in animal foods.

- Possible problems: A deficiency reduces TSH secretion and impairs thyroid function.

- Food sources: Vitamin A is a fatty vitamin found as retinol (in animal foods) or beta-carotene (in plant sources, provitamin A).

- Nutrient absorption: The intestine absorbs essential micronutrients (e.g. iodine, selenium, zinc, iron). Disorders, e.g. leaky gut syndrome, can impair absorption and cause thyroid problems.

- Hormone activation: Certain intestinal bacteria (e.g. Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) support the conversion of T4 into T3.

- Immune system: A disturbed intestinal barrier can promote inflammatory processes and exacerbate autoimmune diseases such as Hashimoto's thyroiditis or Graves' disease.

- Motility, digestion: Hypothyroidism can slow down bowel movements (constipation), hyperthyroidism speeds them up (diarrhea).

- Microbiome composition: Thyroid hormones affect the intestinal flora, which has an impact on nutrient absorption and immune function.

- Diet rich in fiber: Vegetables, fruit and fiber-rich foods (e.g. psyllium husks, flaxseed) promote intestinal health.

- Probiotics, prebiotics: Fermented foods (e.g. sauerkraut, kefir) and prebiotic fiber (e.g. from chicory) support the microbiome.

- Anti-inflammatory foods: Omega-3 fatty acids from fish or nuts can reduce inflammation.

- Avoiding intestinal irritation: Avoiding processed foods, sugar and alcohol strengthens the intestinal barrier.

- Inhibition of iodine uptake: Blocking the sodium iodide symporter (NIS), which means that less iodine is available for hormone production, leads to increased TSH in the long term and possibly to goitre.

- Inhibition of hormone production: The enzyme thyroperoxidase (TPO), which is required for the formation of T3 and T4, is inhibited.

- Promoting the release of iodine: Thiocyanates from tobacco smoke or food release iodine and reduce its availability.

- Cruciferous vegetables: Broccoli, Brussels sprouts, white cabbage, green cabbage and cauliflower contain glucosinolates, which can inhibit iodine absorption and TPO.

- Soy products: Tofu, soy milk and edamame contain isoflavones, which can reduce thyroid hormone production.

- Potatoes, manioc: These contain cyanogenic glycosides, which are broken down into thiocyanates.

- Millet: The C-glycosyl flavones it contains can stimulate hormone synthesis.

Iron

This catalyst of hormone production is an essential co-factor of thyroperoxidase (TPO), which is required for the oxidation of iodine and the synthesis of thyroid hormones.

Vitamin D3

Vitamin D3 regulates the immune system, has an anti-inflammatory effect, protects the thyroid gland from autoimmune processes (e.g. Hashimoto's) and strengthens the immune system.

Vitamin A

As a hormone booster, it supports the release of TSH from the pituitary gland and improves the function of thyroid hormone receptors. Vitamin A is also important for the immune system and cell health.

Influence of the microbiome

The gut-shield gland axis describes the reciprocal connection between the gut and the thyroid gland. The intestine influences the thyroid gland via nutrient absorption, immunological and hormonal mechanisms, while the thyroid gland regulates intestinal function.

Importance of the gut for the thyroid

Influence of the thyroid on the gut

Nutrition tips

Thyroid inhibitors in food

Goitrogenic substances (strumigenes) can impair thyroid function. They are found in certain foods and are particularly effective in people who are sensitive or consume a lot of them. Goitrogenic substances are particularly problematic for people with iodine deficiency or thyroid diseases (e.g. hypothyroidism, Hashimoto's) and for pregnant or breastfeeding women.

How do goitrogenic substances work?

Foods with goitrogenic potential

The following foods have goitrogenic potential, but are safe in moderate amounts, especially with sufficient iodine intake:

Their effect can be reduced by special preparation methods - cooking, blanching or fermentation (breakdown of goitrogenic substances).

Conclusion

The thyroid gland is a central regulator of metabolism and influences every bodily function. Performance and health are inextricably linked to a targeted supply of essential nutrients. Nutrition is therefore not only a supporting factor, but a central component of thyroid health. By consciously selecting and preparing food, many thyroid disorders can be prevented or positively influenced - an impressive example of food as medicine.