- New insights on correcting iron deficiency

- Iron – the multitasker

- Iron deficiency as a global phenomenon

- Dietary iron sources

- The role of hepcidin synthesis

- Problematic immune activation in modern life

- Nutrition strategies for iron deficiency

- Side effects & interactions of iron supplements

- New avenues in iron regulation

- Acting on causal mechanisms

- Conclusion

ENERGY LACK despite spring?

New insights on correcting iron deficiency

Despite the onset of spring, some people experience unexplained tiredness and a persistent lack of drive. Iron deficiency, one of the most common nutrient shortfalls worldwide, can contribute to these symptoms and dampen the start into the warmer months. In this article, we look at why iron matters for the body. From so-called “spring fatigue” to a lack of motivation – seemingly everyday complaints can have serious causes that are worth understanding and addressing.

Iron – the multitasker

Beyond binding oxygen in haemoglobin of red blood cells, iron (in different ionic forms) acts as a cofactor in many enzymatic reactions and supports mitochondrial energy production – the “power plants of the cell”. In short: the entire energy metabolism depends on an adequate iron supply.

The iron metabolism – absorption, regulation and transport – is special compared with minerals like calcium or sodium: the body cannot actively excrete iron and therefore controls status mainly via intake and absorption regulation (1).

The 4–5 g of iron in the human body and daily losses of about 0.5–1.5 mg/day in healthy people can typically be compensated through diet, even though absorption averages only ~6% in men and ~12% in women (2).

Because of irons tight link to mitochondrial energy production, a deficit impacts performance and can trigger symptoms such as:

- Listlessness

- Pale skin

- Fatigue

- Poor concentration

- Susceptibility to infections

- White ridges on fingernails

- Increased hair loss

- Cracked corners of the mouth

- Headaches

- Dizziness

These general symptoms and often missing diagnostics mean iron deficiency frequently goes untreated.

Iron deficiency as a global phenomenon

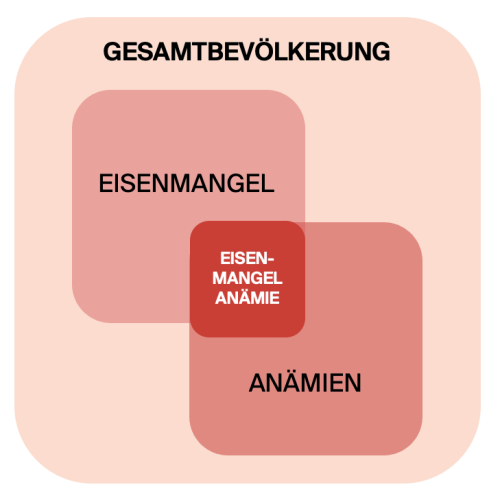

Globally, iron deficiency is the most common and widespread nutrition-related insufficiency (3). Epidemiology of iron deficiency anaemia shows: About a quarter of the worlds population suffers from iron-deficiency anaemia. Preschool children are most affected (>47%), while men show the lowest prevalence (~13%) (4).

At-risk groups for latent to manifest iron deficiency up to anaemia include people in growth phases (children) (5), women of reproductive age (menstrual losses), pregnant women (increased demand), breastfeeding women, athletes (higher turnover), people with low-iron and low-vitamin-C diets, and those with inflammatory conditions that consume iron (6) (Fig. 1).

Even iron deficiency without anaemia already strains the organism. Optimal iron status matters for performance in sport and everyday life. A key diagnostic parameter is the storage marker serum ferritin (7). But ferritin alone is not enough: transferrin and transferrin saturation should be part of standard labs to detect latent deficiency without anaemia – which can still explain fatigue, exhaustion and low energy.

Dietary iron sources

Beyond under- and malnutrition, physiological and pathophysiological processes alter how well iron is absorbed.

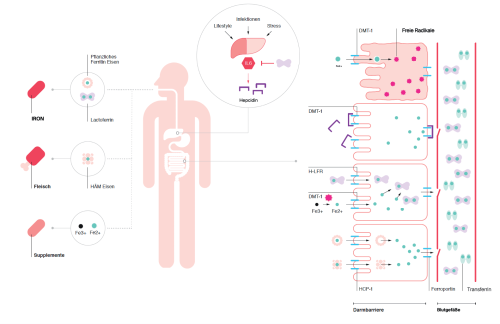

Dietary iron is absorbed into intestinal epithelial cells via the transporter DMT1 (for Fe2+), but other forms can enter through specific channels. In animal foods (e.g. meat), iron is present as heme iron and can be absorbed via the HCP-1 transporter (8). Plant iron is often stored as ferritin and can also be taken up through a separate pathway.

The role of hepcidin synthesis

If low intake is not the cause, consider absorption. The body self-regulates absorption and may inhibit it under certain conditions: during inflammation, immune cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6. Via circulation these reach the liver and stimulate production of hepcidin, a peptide that regulates (inhibits) iron uptake by binding to the exporter ferroportin. Ferroportin normally exports iron from enterocytes, hepatocytes and macrophages into the blood. When hepcidin binds, iron remains trapped in cells and is unavailable for metabolism (9).

From an evolutionary angle this makes sense: for our ancestors, elevated interleukin-6 usually signalled bacterial infection (10). Bacteria also require iron to proliferate. If iron is sequestered, pathogens replicate less, helping the immune system clear them faster – even if this temporarily hampers the hosts own metabolism.

Problematic immune activation in modern life

This protective mechanism is tricky today: psychoneuroimmunology and stress research show many non-infectious triggers can activate the immune system (11), including:

- Lifestyle factors

- Pro-inflammatory diet

- Physical inactivity

- Excess training

- Sleep deprivation

- Environmental toxins

- Chronic psycho-emotional stress

These “low-grade” inflammations dont look like an acute infection but create chronic activation. Theyre linked to many non-communicable chronic and degenerative diseases (12).

Chronic immune activation elevates hepcidin and thus causes chronic iron distribution problems, potentially leading to anaemia of inflammation (13) (Fig. 2).

Nutrition strategies for iron deficiency

Start with a species-appropriate, balanced diet. Many foods contain iron, but bioavailability differs by storage form. Meal composition also strongly affects absorption: plant compounds such as phytates and polyphenols in tea and coffee impair absorption; so does calcium (e.g. dairy). Conversely, pairing plant iron with ascorbic acid (vitamin C) enhances uptake by preventing conversion to poorly absorbed forms (14).

Side effects & interactions of iron supplements

If diet is insufficient, oral iron supplements are indicated. However, ferrous iron Fe2+ in enterocytes increases formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). When larger amounts of free Fe2+ are present, the Fenton reaction with hydrogen peroxide generates hydroxyl radicals to convert Fe2+ to Fe3+ for transport – but excess radicals can induce programmed cell death (15).

An iron chelator can down-regulate this process (16). More cell death damages the gut barrier and is linked to typical side effects (17). Patients know these as constipation, nausea, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, vomiting, heartburn and dark stools (18). To reduce side effects, ferric Fe3+ preparations are used; theyre often better tolerated but must be reduced to Fe2+ before uptake (lower bioavailability) and can still promote radicals in the lumen (19).

New avenues in iron regulation

Based on physiology of iron handling, research is exploring alternatives: lactoferrin, an iron-binding glycoprotein produced by immune and gland cells, belongs to the transferrin family, naturally transports iron and can influence iron homeostasis. As an immune protein, it also supports host defence with antibacterial, antiviral and antifungal properties (20).

Lactoferrin modulates immunity and can correct dysfunction (21). It occurs in higher amounts in mammalian milk. Bovine lactoferrin from cows milk is structurally and functionally very similar to human lactoferrin (22). Extraction from milk is the common way to obtain larger quantities for preventive/therapeutic purposes. Because the molecule is highly reactive, purification quality is crucial for function and bioavailability (23).

Acting on causal mechanisms

With anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects (24), lactoferrin can dampen chronic inflammation. In vitro, it down-regulates cytokines such as interleukin-6 that drive hepcidin synthesis (25). First clinical data in pregnant women with iron-deficiency anaemia support this (26). A 2022 meta-analysis found lactoferrin improved serum iron, ferritin and haemoglobin more than ferrous sulfate, while reducing fractional iron absorption issues and interleukin-6 levels (27).

Conclusion

Iron is critical for energy metabolism and vitality. A balanced diet and, if needed, targeted measures can counter deficiency. Emerging approaches like lactoferrin show promising results and may broaden treatment options in the future.

__________________________

References

(1) Vaulont S, et al: Of mice and men – The iron age. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2079–2082.

(2) Kaltwasser JP, et al: Eisenmangel und andere hypoproliferative Anämien. Harrisons Innere Medizin. Berlin. 2003:733.

(3) WHO: Iron Deficiency Anaemia Assessment, Prevention and Control – A guide for programme managers. 2001.

(4) Durrani AM: Prevalence of Anemia in Adolescents – A Challenge to the Global Health. Acta Scientific Nutritional Health. 2018;2(4):24–27.

(5) Grant CC, et al: Population prevalence and risk factors for iron deficiency in Auckland, New Zealand. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2007;43:532–538.

(6) Lee JO, et al: Prevalence and Risk Factors for Iron Deficiency Anemia in the Korean Population – Results of the Fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:224–229.

(7) Knovich MA, et al: Ferritin for the Clinician. Blood Rev. 2009 May;23(3):95–104.

(8) Sharp P, et al: Molecular mechanisms involved in intestinal iron absorption. World J Gastroenterol. 2007 Sep 21;13(35):4716–4724.

(9) Cherayil BJ: Iron and Immunity – Immunological Consequences of Iron Deficiency and Overload. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2010;58:407–415.

(10) Andrews SC, et al: Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:215–217.

(11) Rohleder N: Stimulation of Systemic Low-Grade Inflammation by Psychosocial Stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2014;76:181–189.

(12) Liu YZ, et al: Inflammation – The Common Pathway of Stress-Related Diseases. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2017 June:Article 316.

(13) Ganz T, et al: Iron imports – Hepcidin and regulation of body iron metabolism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:199–203.

(14) Zijp IM, et al: Effect of Tea and Other Dietary Factors on Iron Absorption. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2000;40(5):371–398.

(15) Eid R, et al: Iron-mediated toxicity and programmed cell death – A review. BBA. 2017;1864:399–430.

(16) Ward PP, et al: Lactoferrin – Role in iron homeostasis and host defense. BioMetals. 2004;17:203–208.

(17) Kortman G, et al: Nutritional iron turned inside out – intestinal stress from a gut microbial perspective. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014;38:1202–1234.

(18) Tolkien Z, et al: Ferrous Sulfate Supplementation Causes Significant GI Side-Effects in Adults – Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis. PLOS One. 2015.

(19) Behnisch W, et al: S1 guideline 025-021 – Iron-deficiency anaemia. AWMF online. 2016(1).

(20) Chen PW, et al: Influence of Bovine Lactoferrin on the Growth of Selected Probiotic Bacteria. Biometals. 2014;27(5):905–914.

(21) Puddu P, et al: Immunomodulatory effects of Lactoferrin on antigen presenting cells. Biochemie. 2009;91:11–18.

(22) Valenti P, et al: Lactoferrin – host defence against microbial and viral attack. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2576–2587.

(23) Moradian F: Lactoferrin, Isolation, Purification and antimicrobial effects. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2011(8).

(24) Legrand D: Overview of Lactoferrin as a Natural Immune Modulator. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2016:173.

(25) Cutone A, et al: Lactoferrin counteracts inflammation-induced changes of iron homeostasis in macrophages. Front Immunol. 2017;6(8):705.

(26) Paesano R, et al: Oral lactoferrin in pregnant women with iron deficiency/anaemia – effects on iron homeostasis. Biochimie. 2009;91:44–51.

(27) Zhao X, et al: Oral Lactoferrin vs Ferrous Sulfate for Iron-Deficiency Anemia – Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2022;14(3):543.