Electrolytes: The invisible directors of our body

Whether during exercise, in summer heat or when you are ill – the term electrolytes keeps coming up, yet only few people really know what it means. In reality, electrolytes are key building blocks of our body. Without them, our nerves would not fire, our muscles would not contract and our heart would not beat a single time. In this article, we dive into the scientific basics of electrolytes and show why they are so crucial for health and performance.

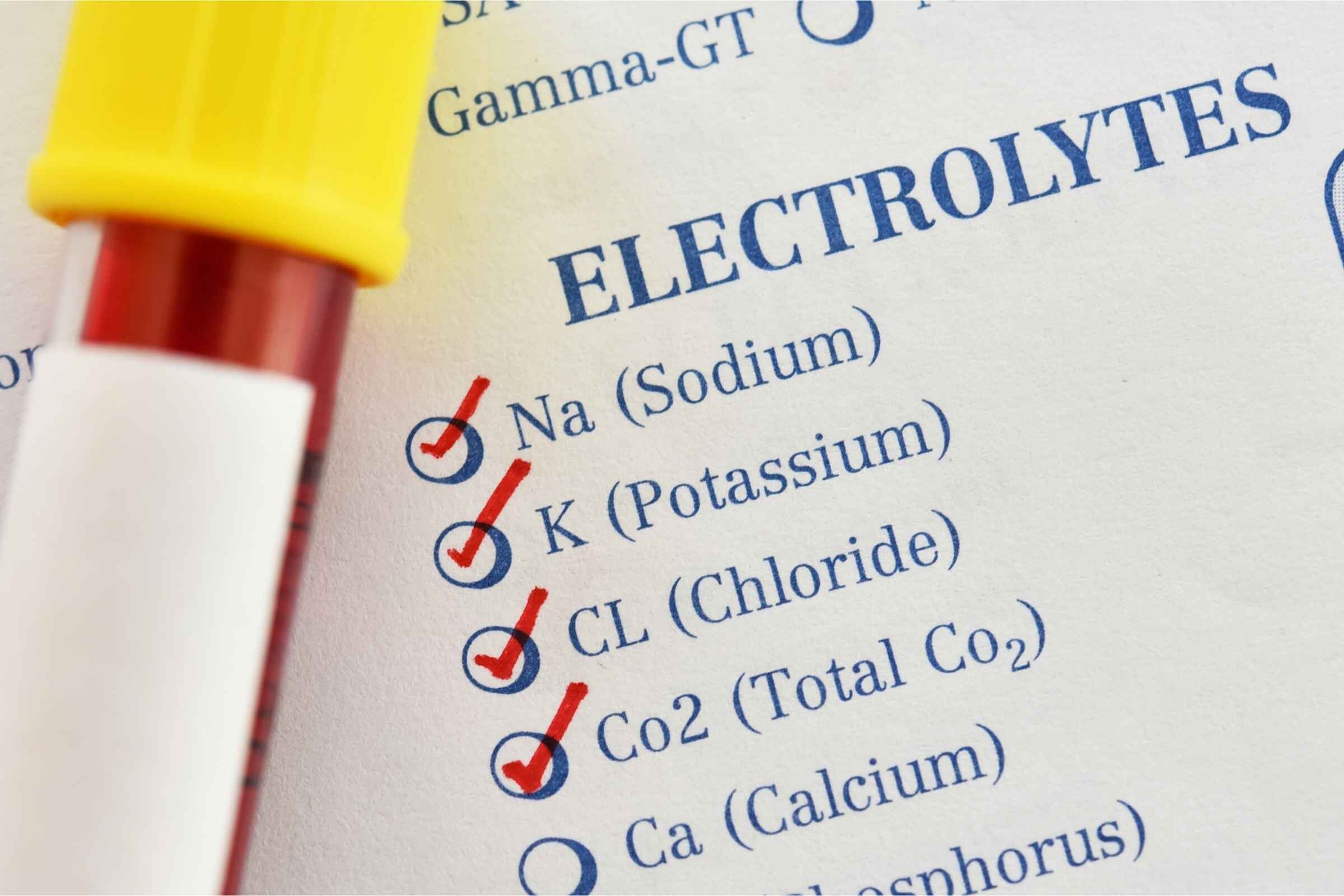

What are electrolytes?

Electrolytes are electrically charged particles (ions) that are dissolved in body fluids. The most important electrolytes in the human body are:

- Sodium (Na⁺)

- Potassium (K⁺)

- Calcium (Ca²⁺)

- Magnesium (Mg²⁺)

- Chloride (Cl⁻)

- Phosphate (PO₄³⁻)

- Bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻)

These ions are formed by the dissolution of salts in water – a natural chemical process. A typical example is table salt (sodium chloride): it consists of tiny crystals in which positively charged sodium ions and negatively charged chloride ions attract each other and are tightly bound together.

If you add salt to water, something remarkable happens. The water molecules (which are themselves slightly charged) surround the salt crystals and break these bonds. As a result, the sodium and chloride ions separate from each other and move freely in the water.

This process is called dissociation. It creates charged particles, so-called electrolytes, that can move through the fluid. This is also why a salt solution conducts electricity, whereas pure water conducts almost no current.

Depending on the salt, this dissolution can be almost complete (for "strong electrolytes" such as table salt) or only partial (for "weak electrolytes" such as acetic acid). For our body this is crucial, because only freely dissolved ions can perform tasks such as nerve conduction, muscle contraction or regulation of fluid balance. [1]

Why are electrolytes essential for life?

Electrolytes regulate key processes in the body, including:

1. Maintaining fluid balance

Regulation of the body’s water balance is closely linked to electrolyte balance. Sodium is the main positively charged ion outside the cells (in the so-called extracellular space). It plays a major role in holding and shifting water in the body.

The mechanism behind this is called osmosis: water moves to where the concentration of dissolved particles – mainly sodium – is higher. If sodium levels in the blood rise, water moves out of the bodys cells into the extracellular space and into the bloodstream. This has two important effects:

- Blood volume and blood pressure increase: the circulating blood volume rises as water follows sodium into the bloodstream. Sodium balance is therefore tightly regulated by the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and hormones such as aldosterone and ADH (antidiuretic hormone).

- Cell hydration changes: if there is too much sodium outside the cells, it draws water out of them. Cells can effectively start to "dry out" – a state that can occur, for example, with heavy sweating without adequate fluid and electrolyte replacement.

An imbalance in fluid and sodium balance can lead to hyponatremia (too little sodium) or hypernatremia (too much sodium), both of which may cause serious neurological or cardiovascular complications. [2]

2. Nerve and muscle function

Our nerves and muscles work like biological electrical circuits, and electrolytes are their switching elements. Every nerve cell has a cell membrane across which there is an electrical voltage gradient. This is created by an uneven distribution of ions, especially sodium, potassium and calcium.

At rest, the inside of the nerve cell is negatively charged compared to the outside. When the cell is stimulated, ion channels open and sodium flows into the cell while potassium flows out. This leads to a rapid reversal of the membrane potential, known as an action potential.

This electrical impulse travels along the nerve until it reaches, for example, a muscle cell. There, calcium ensures that the muscle fibers contract – the basis of every movement, from smiling to your heartbeat.

If even one of these electrolytes is lacking, the system no longer works properly. A deficiency of potassium or calcium can lead to muscle cramps, weakness or paralysis and cardiac arrhythmias. [3]

3. Acid–base balance

The human body functions properly only within a very narrow pH range (7.35–7.45). Even small deviations can inhibit enzymes, damage organs or become life-threatening. Here, bicarbonate ions are crucial as the most important buffer system in the blood.

If there are too many hydrogen ions (acids) in the blood, they bind to bicarbonate to form carbonic acid. This then breaks down into water and carbon dioxide, which is exhaled via the lungs. Conversely, in the case of an excess of bases, the body can release hydrogen ions to stabilise the pH. The kidneys play a central role here: they excrete acids or bases as needed and can produce new bicarbonate.

A disturbed acid–base balance can manifest as acidosis (blood too acidic) or alkalosis (blood too alkaline) with symptoms such as shortness of breath, dizziness, confusion or heart problems. Regulation via electrolytes is therefore vital for the bodys chemical equilibrium. [4]

Electrolyte losses – when does it become critical?

The body loses electrolytes mainly through sweat, urine, vomiting and diarrhoea. During intense physical activity or high temperatures, deficits can develop quickly. [5]

Symptoms of electrolyte imbalance

The body often reacts to electrolyte losses gradually – many warning signs go unnoticed at first. Common symptoms include:

- Muscle cramps and twitching: especially with potassium or magnesium deficiency, which are essential for conduction in muscle cells

- Fatigue and weakness: often due to sodium or potassium loss impairing normal cell function

- Heart rhythm disturbances: particularly with too little potassium or magnesium, as the heart is highly dependent on precise electrical signals

- Reduced concentration and coordination: common signs of hyponatremia or dehydration

1. Loss through sweat

During intense exercise or heat, we lose not only water but also significant amounts of sodium, chloride and potassium through the skin. Sweat contains on average about 40–60 mmol/l sodium. With prolonged sweating without replacement (for example via sports drinks or salty foods), blood sodium levels can drop.

2. Loss through urine

The kidneys finely regulate how many electrolytes are excreted, controlled by hormones such as aldosterone and ADH. With very high fluid intake or certain medications (e.g. diuretics), excessive electrolyte loss can occur.

3. Loss through vomiting and diarrhoea

These acute gastrointestinal events often lead to rapid and marked electrolyte losses – especially of chloride, potassium and bicarbonate. This can cause not only dehydration, but also a disturbed acid–base balance.

Where does the body get electrolytes from?

The main sources are foods and drinks:

| Electrolyte | Main dietary sources | Especially important in: |

| Sodium | Table salt, salted foods | Heavy sweating, diarrhoea, vomiting |

| Potassium | Bananas, spinach, potatoes | Intense exercise, kidney disorders |

| Calcium | Dairy products, broccoli | Growth, pregnancy, osteoporosis |

| Magnesium | Nuts, whole grains | Stress, chronic disease |

| Chloride | Sea salt, tomatoes | Dehydration, strong heat |

| Phosphate | Meat, legumes | Phosphate deficiency, high energy demand |

A balanced diet usually covers daily needs. Under special conditions (sports, heat, illness), electrolyte solutions can be helpful.

Electrolytes in sports – more than just marketing?

Sports drinks often advertise "important electrolytes", but not all products deliver what they promise. The crucial point is the right balance of sodium, potassium and fluid, particularly during longer efforts. There are indeed strong scientific reasons why athletes should pay attention to electrolytes – but also some persistent misconceptions.

1. Why electrolytes matter during exercise

During physical activity – especially when it lasts longer than 60 minutes – the body loses not only water but also significant amounts of sodium, potassium, chloride and smaller quantities of other ions through sweat. On average, sweat contains per litre:

- Sodium: about 30–60 mmol/l

- Chloride: about 30–50 mmol/l

- Potassium: about 4–8 mmol/l

These losses affect muscle contraction, nerve conduction and fluid balance. If they are not replaced, this can lead to dehydration, muscle weakness, cramps or, in extreme cases, a complete drop-off in performance.

2. Water alone is not enough

A common mistake during endurance activities is to drink only water. This can further dilute the salt content of the blood and lead to hyponatremia, particularly in long-distance events such as marathons or triathlons. Studies such as the position stand by Sawka et al. (2007) show that hypotonic or sodium-containing drinks can help to maintain performance and prevent dangerous electrolyte disturbances.

3. What should a good sports drink contain?

Not all sports drinks are well formulated. An effective drink for prolonged activity (longer than 1 hour) should contain:

- Sodium: 300–700 mg/l – to support fluid absorption and prevent hyponatremia

- Potassium: 100–200 mg/l – to support muscle and nerve function

- Carbohydrates: 4–8% – to provide energy without slowing gastric emptying

- Hypotonic or isotonic composition – for quick gastric emptying and good absorption

4. Consider individual differences

Both sweat rate and sweat sodium concentration vary widely between individuals. They depend on genetics, training status, climate and clothing. For this reason, individual testing (e.g. sweat tests) can be useful, especially for ambitious athletes. [6]

Conclusion

Electrolytes are far more than a buzzword from sports marketing. They are fundamental building blocks for the smooth functioning of our body – from cellular hydration and signal transmission in nerves and muscles to the regulation of blood pH.

During intense physical activity, illness or summer heat, electrolyte requirements can change quickly. Anyone who takes symptoms such as muscle cramps, fatigue or concentration problems seriously can detect a potential imbalance early. A balanced diet generally supplies all essential electrolytes, but under special conditions – for example in endurance sports or with significant fluid loss – targeted supplementation can be decisive.

Being mindful of your electrolyte status not only supports physical performance but also protects against serious health complications. If you take care of your electrolytes, you actively stabilise your inner systems – invisible, yet indispensable.

______________________

References

[1] Atkins, P., & de Paula, J. (2014). Atkins' Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press.

[2] Guyton, A.C., & Hall, J.E. (2021). Textbook of Medical Physiology. Elsevier.

[3] Bear, M.F., Connors, B.W., & Paradiso, M.A. (2020). Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain. Wolters Kluwer.

[4] Kraut, J.A., & Madias, N.E. (2010). Metabolic acidosis: pathophysiology and diagnosis. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(13), 1229–1236.

[5] Adrogué, H.J., & Madias, N.E. (2000). Hyponatremia. New England Journal of Medicine, 342(21), 1581–1589.

[6] Sawka, M.N., et al. (2007). American College of Sports Medicine position stand: exercise and fluid replacement. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 39(2), 377–390.